Blockchain forensics is the trusted informant in crypto crime scene investigation

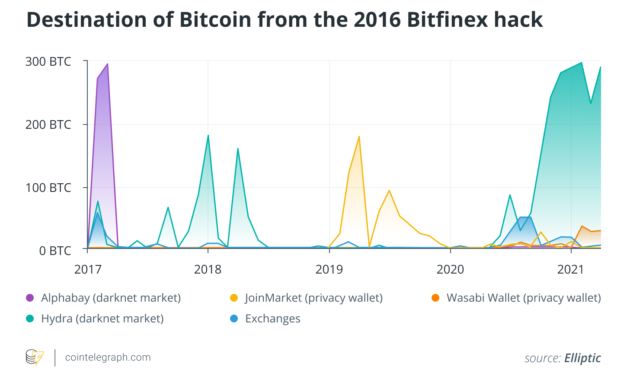

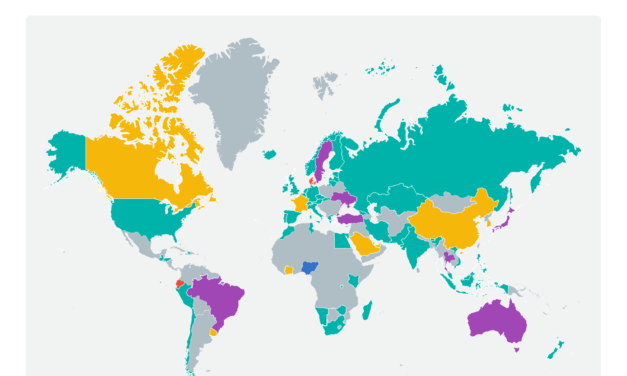

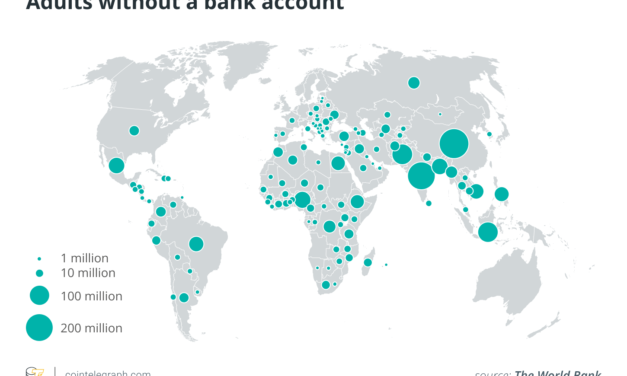

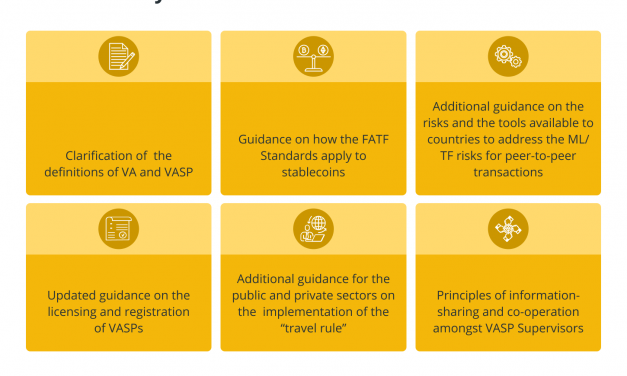

The seizure by the U.S. Department of Justice of $3.6 billion worth of Bitcoin (BTC) lost during the 2016 hack of Bitfinex’s cryptocurrency exchange has all the ingredients of a Hollywood film — eye-popping sums, colorful protagonists and crypto cloak-and-dagger — so much so that Netflix has already commissioned a docuseries. But, who are the unsung heroes in this action-packed thriller? Federal investigators from multiple agencies including the new National Cryptocurrency Enforcement Team have painstakingly followed the money trail to assemble the case. The Feds also seized the Colonial Pipeline ransoms paid in crypto, making headlines last year. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) seized $3.5 billion worth of crypto in 2021 in non-tax investigations, according to the recently released Chainalysis cryptocrime 2022 report. The trends point to the diminishing ability of nefarious criminals and terrorists to use cryptocurrencies as safe havens to stash their ill-gotten gains, illicit profits, donations and funding away from law enforcement officials. For example, the Bitfinex hackers are reported to have moved a small portion of Bitcoin to darknet exchange Alphabay and from there to regular crypto exchanges. This is one of the leads that the Feds used to apprehend the defendants.Related: How will DOJ’s new crypto enforcement team change the game for industry players, good and bad?Law enforcement agencies are getting better at investigating crypto crimesRegulators and law enforcement agencies in a select few countries have really upped the ante on blockchain forensics. Although initially lost at sea, some G-men and women have honed the playbook on the search and seizure of assets, prosecution in courts and disposal of seized digital currency after winning the case. Each of these specific steps demonstrates a deep understanding of this disruptive technology.There are several considerations during the process of investigation, and all require an intimate knowledge of the blockchain space. The blockchains may be transparent but various techniques such as tumblers, mixers, chain hopping and structuring (doing multiple small transfers to avoid scrutiny) must be understood and analyzed. The suspects may be apprehended physically but law enforcement officials must also ensure that digital assets are not moved out of reach by the defendants or by their alleged accomplices. The seized crypto assets must be safely in custody during the pending case. Related: Crypto in the crosshairs: US regulators eye the cryptocurrency sectorThe financial cops certainly do not want the crypto assets stolen while the case is being prosecuted. Usually, confiscated crypto assets are auctioned and the proceeds go into designated government accounts. But, when there are innocent victims, a process for restitution is essential for there to be trust in the judicial system. Blockchain forensics is a part of the larger digital forensics domainBlockchain analysis and forensics do not live alone on a deserted island. There are several layers of collaboration required to bring wrong-doers to justice. Firstly, the growing success of law enforcement in tracking crypto crimes is due to the tightening of Know Your Customer (KYC) norms of entities that handle fiat to crypto and crypto to fiat currency conversions. Then, there are other digital forensic technologies involved, for example, gathering data and evidence from seized mobile phones and computers.Next, there are private sector partners that support crypto monitoring, enforcement actions and cases. There are now several companies that provide tools for blockchain intelligence such as identifying tainted wallets, assigning risk scores to wallet addresses, using analytics and artificial intelligence techniques to flag suspicious patterns and much more. With such tools and techniques, investigative agencies can be more effective. Armed with KYC information as per Anti-Money Laundering (AML) laws, prosecutors and their colleagues in regulatory agencies involving securities, commodities, tax and currency matters pursue the inquiries in the real off-chain world.Related: Lost Bitcoin may be a ‘donation,’ but is it hindering adoption?International collaboration is also critical. Criminal actors would like to keep their assets out of reach of the long arm of the law. Law enforcement agencies need to collaborate with partner agencies in other countries. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) which helps harmonize rules and assists in the prosecution of money laundering and stems the funding of terrorism is an important inter-governmental policymaking body. It has made recommendations regarding virtual assets, for example, the case of the Travel Rule, but countries are still in different stages of implementing them. Such are the vagaries of sovereignty and statehood in a financial world in transition, the rules of engagement for which are still under development.Blockchain forensics expertise is unevenly distributedThe recent success of the agencies in the U.S. and a few other countries’ may give the impression that law enforcement agencies everywhere are on top of blockchain forensics. In reality, specialist teams, armed with state-of-the-art blockchain analysis tools, are the exception. Many national agencies have yet to begin building capabilities in this area.Related: FATF guidance on virtual assets: NFTs win, DeFi loses, rest remains unchangedAs of 2022, more than 50 countries have instituted either absolute or implicit bans on cryptocurrencies. Ironically, even countries that ban crypto or look at them askance will need to master blockchain analysis because digital assets easily cross borders. Watch for law enforcement agencies to hire more blockchain specialists and White Hat hackers. The intricate dance involved in investigating the Bitfinex hack shows that they might even become BFFs. With financial crimes, the mantra for the legal authorities has always been to “follow the money.” The public nature of blockchain transactions actually makes it easier to track and trace criminal activity. Working with technologists who know what they are doing makes it even easier.Crypto libertarians may not like the increased involvement of investigative agencies in the space but the writing on the wall is clear: Such guardrails are better for all involved, consumers and crypto companies alike. The industry cannot be worth trillions of dollars and not attract the watchful eye of regulators.This article was co-authored by Kashyap Kompella and James Cooper.This article does not contain investment advice or recommendations. Every investment and trading move involves risk, and readers should conduct their own research when making a decision.The views, thoughts and opinions expressed here are the authors’ alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views and opinions of Cointelegraph.Kashyap Kompella, CFA, a technology industry analyst, is CEO of RPA2AI, a global artificial intelligence advisery firm. Kashyap has a bachelor’s degree (honors) in electrical engineering, an MBA and master’s in business laws. He is also a CFA Charter holder. Kashyap is the co-author of Practical Artificial Intelligence: An Enterprise Playbook.James Cooper is professor of law at California Western School of Law in San Diego and research fellow at Singapore University of Social Sciences. He has advised governments in Asia, Latin America and North America for more than two and a half decades on legal reform and disruptive technologies. A former contractor for the U.S. Departments of Justice and State, he advises blockchain and other technology companies.

Čítaj viac