The SEC is bullying Kim Kardashian, and it could chill the influencer economy

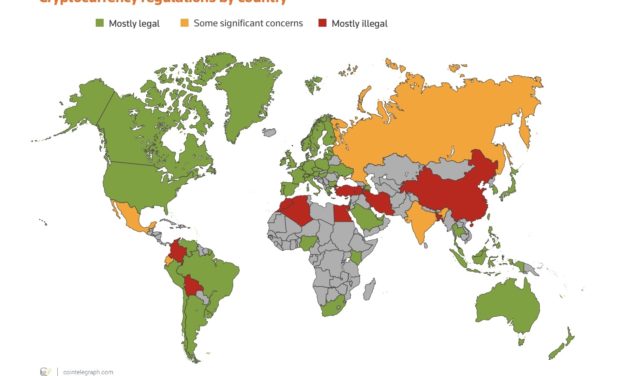

The Securities and Exchange Commission announced on Oct. 3 that Kim Kardashian settled an allegation that she promoted “a crypto asset security offered and sold by EthereumMax without disclosing the payment [of $250,000] she received for the promotion.” While she cooperated and closed the case with $1.26 million in penalties, the charge highlights the liability that “influencers” increasingly face as a result of an activist SEC that has failed to establish regulatory clarity.Pushing influencers to leave the United StatesAddressing the agency’s action against Kardashian, Jacob Robinson, a legal scholar and host of the Law and Code podcast, noted that “The net-positive is [that] this probably leads to less shilling by celebs who have zero knowledge of the underlying project & are just receiving a big payday.”Thanks to the proliferation of social media platforms, content creators and influencers have emerged and are working with brands to promote products and services. Sadly, the “creator economy” has also had downsides. In particular, influencers have often sold products and services that may not serve everyone’s interests, accepting payment from companies in exchange for their support.While that privilege can be, and often is, abused, influencers are not doing anything systematically different than what corporations do when they take out paid advertisements in the media and on television, or even when board members join and take on a retainer to share their network and promote an organization. When a corporation takes out an ad in a large paper or magazine, such as The New York Times or Vogue, are the media outlets equally liable for not disclosing their acceptance of payment to all the readers? Clearly not, and the media’s business model would quickly crumble if they were unable to accept such paid advertising opportunities.Related: Biden’s anemic crypto framework offered nothing newSo, why are influencers treated so differently, and why can they personally be liable and targeted by a federal agency? Consider the car market: If a used car salesperson sells a customer a car that is later recalled or turns out to have some other flaw, are they singled out by a regulatory agency? The car company might be — as we have seen with Volkswagen, Toyota and others over the years — but the individual employee is generally free from such liability.The SEC’s action against Kardashian risks alienating and stifling other members of the creator economy. While she can “afford” the $1.26 million fine — a little more than $1 million in excess of what she earned — many content creators are not making six-figure-plus salaries each year. The action also threatens to push many content creators outside the United States to countries that have more favorable policies.Defining securities and liabilityThe SEC has adhered to an old Supreme Court ruling from 1946, SEC v. W. J. Howey Co., which led to what is now known as the “Howey test.” The Howey test defines an “investment contract” if the following conditions are met: 1) an investment of money 2) in a common enterprise 3) with the expectation of profit 4) derived from the efforts of others. The test, however, was introduced in an entirely different economy than the one we have today. To be sure, many projects that involve the release of fungible tokens easily fall into the category of a security regardless of how liberal one wants to be with the definition. But other projects, especially nonfungible token projects, are in a much grayer area. Many NFT projects do not convey any expectation of profit to their potential holders but rather emphasize perks and exclusive access to events, classes or deals.Related: Get ready for the feds to start indicting NFT tradersAdmittedly, the SEC’s recent regulatory action went after Kardashian for her promotion of EthereumMax (EMAX) without disclosing that she had received payment rather than for EthereumMax being a security, as it was arguably an easier, more clear-cut case. But the case highlights a major challenge influencers will inevitably face in the Web3 economy if they have to worry about regulatory risk against themselves for promoting different projects, even if they just make a social media post.Other countries are taking a vastly different approach toward Web3. For example, the United Arab Emirates has gone on record saying that it wants its economic success to be measured according to its “gross metaverse product” rather than the conventional gross domestic product that has become the norm for cross-country comparisons in productivity. The UAE, among others (such as Singapore), has become a hub for entrepreneurs and startups.What happened to Kardashian could happen to othersIf the regulatory concern is that influencers are abusing their authority by promoting products and services without disclosing receipt of compensation, then Web3 lends itself perfectly through greater transparency and accountability on the blockchain. In particular, influencers could have their digital wallets open for viewing so that their remuneration is open and their own purchases visible. (There is still a need for privacy-preserving blockchains since everything in everyone’s lives should not be on full display, but with the blockchain, there is much more potential for transparency and accountability where it matters.)Web3 also allows content creators to receive payment for their creative content without having to rely as much on centralized entities for brand deals and partnerships. NFTs, for instance, allow artists to transform audiences into communities that engage with their content directly.What happened to Kardashian could have happened to several influencers. While regulatory actions without penalties admittedly do not have much bite — and often, such penalties are needed to signal that an agency is serious — an alternative strategy would have been to reach out to Kardashian and galvanize support among a body of influencers to establish stronger, more transparent norms around the promotions of products and services, particularly crypto projects that could be classified as securities. Such an approach is more collaborative and would contribute to establishing shared norms and best practices among crypto enthusiasts.Christos Makridis is an entrepreneur, economist and professor. He serves as chief operating officer and chief technology officer at Living Opera, a Web3 multimedia startup, and holds academic appointments at Columbia Business School and Stanford University. Christos also holds doctorates in economics and management science from Stanford University.This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal or investment advice. The views, thoughts and opinions expressed here are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views and opinions of Cointelegraph. The author was not compensated by any of the projects cited in this piece.

Čítaj viac